By Hsiao-Ting, LI

In today’s world, where almost everyone owns a smartphone, the concept of “photography” is both well-known and somewhat ambiguous to the general public. We see everything from everyday moments captured with phones to artful works by established photographers that utilize various techniques and narratives. These images are everywhere, found on social media platforms and in our daily lives. When examining the current photography environment in Taiwan, it becomes evident that this popular creative medium has not been fully integrated into the academic system. While numerous photography activities take place across the island, they seem to lack a cohesive framework. Although various educational resources and photography programs exist, they are not systematically integrated into the educational system as other creative media are. Even in such an environment, a group of individuals remained passionate and dedicated to photography, leading to the establishment of the “Lightbox Photo Library” in 2015.

Taiwan Photo Enthusiasts’ Image Lightbox – Lightbox Photo Library

“After examining the origins of photography and libraries, we aim to maintain their free, open, and public-oriented nature in Taiwan. Accordingly, we decided to operate as a non-profit organization with a ‘Free to All’ approach, focusing on the photography publications of Taiwan and dedicating ourselves to collection and organization efforts,” said director Tsao Liang-pin. Although the Lightbox Photo Library team had considered implementing a membership system or charging entrance fees as potential revenue sources, their primary goal was to foster an information-sharing culture. To preserve the openness of the space and facilitate a platform for bidirectional exchange, they ultimately decided to operate the library as a non-profit arts organization. They plan to sustain it through public fundraising, as well as donations from individuals and the public and private sectors. Before their relocation, the Lightbox Photo Library had gathered several thousand visitors who engaged in activities and read books within its 30-square-meter space. As their collection expanded and the community grew, the need for a larger location became increasingly pressing in the following years.

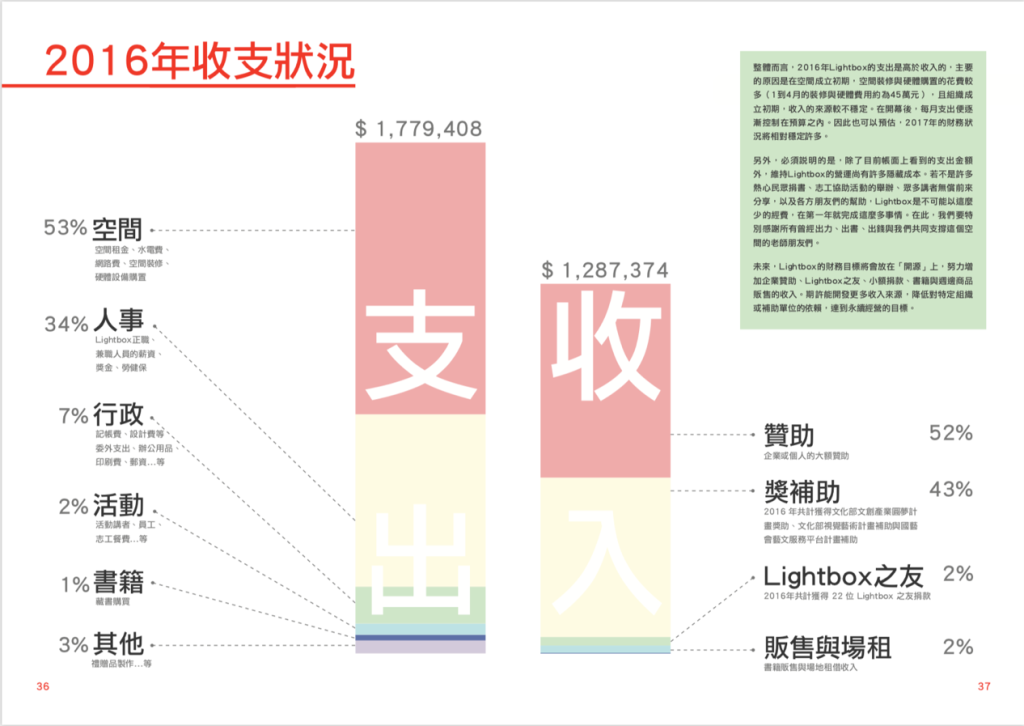

The expenses associated with relocating to a larger space were very high, and the team members lacked experience in managing such transitions. As they confronted the financial challenges of moving and renovating the interior, library members discussed all possible solutions. Previously, Lightbox primarily relied on individual sponsorship for funding, in addition to government grants. Before finalizing a fundraising plan, the team discussed several viable options, including the possibility of applying for grants. However, they found that there were no precedents for library renovation grants, and no relevant categories could be identified within the various funding mechanisms offered by the Ministry of Culture, Taipei City Bureau of Cultural Affairs, and the National Culture and Arts Foundation, among others. Furthermore, the available grant amounts would only cover a portion of the relocation costs. Lightbox’s 2016 annual report financial statements indicate that relying on grants for relocation funding is likely to face greater challenges.

Figure 1 Lightbox 2016-17 Annual Report

Expenditure – $1,779,408

- 53% Space

- Rent, utilities, repairs, etc.

- 34% Personnel

- Salaries, labor insurance, health insurance, etc.

- 7% Administration

- Office supplies, accounting, printing, etc.

- 2% Activities

- Event-related expenses

- 1% Publications

- Book production costs

- 3% Others

Income – $1,287,374

- 52% Donations

- 43% Grants

- 2% Lightbox Friends

- 2% Merchandise & Space Rental

The hardware in the space, including bookshelves and displays, was specifically designed and measured for storing photography materials and books. Creating something from nothing—whether design or construction—required significant resources, and there were no grants specifically for renovation and relocation projects. Hearing that the nearby Aiyue Second-hand Bookstore had successfully secured relocation funding through crowdfunding left a deep impression on team members, opening a new door for securing relocation funding. However, none of the team members had experience with crowdfunding. The team’s closest experience was with a book donation campaign. Unlike book donation, crowdfunding has already reached a certain economic scale. Although arts groups, venues, and non-profit organizations have recognized the potential of crowdfunding, the challenge remains: how to encourage consumers to invest their money in sponsoring projects and supporting a space that promotes public engagement. This understanding will be crucial for the success of Lightbox Photo Library’s crowdfunding campaign.

After evaluating various crowdfunding platforms in Taiwan, Lightbox chose to collaborate with the consulting company “Backer-Founder.” “Backer-Founder” assisted Lightbox in evaluating the various advantages and conditions associated with the relocation fundraising project and its space. To minimize costs during the fundraising process, the space’s members decided to manage and design the fundraising project independently. This allowed “Backer-Founder” to act as the brain, offering advice and making strategic decisions, while Lightbox would take on the hands-on implementation. As a result, the space only needed to cover the consultation fees for the fundraising project.

Crowdfunding Benefits

Crowdfunding has become a channel that startup companies consider when needing funding in recent years. However, the benefits of crowdfunding extend beyond just funding; numerous associated advantages are often overlooked by traditional fundraising methods. Excluding high-risk products that require endorsements from trusted experts or celebrities, consumers typically first consider the number of participants and the current fundraising amount when engaging with crowdfunding. From the perspective of other consumers, this information serves as an endorsement for the fundraising project—the more people willing to participate, the more likely it is to be a successful product.

While a reward system is in place to provide backers with incentives for reaching milestone goals, consumers do not participate in fundraising solely to obtain these reward items. Those are simply symbolic tokens; what truly motivates consumers to invest in crowdfunding projects is the idea behind the project. Effectively spreading awareness and understanding of a project’s concept to successfully promote a fundraising campaign has become a specialized business, leading to the emergence of crowdfunding consulting companies that guide proposers in this endeavor. Photography tells stories through images, whereas “Backer-Founder” provided Lightbox with various methods and channels to effectively convey the library’s compelling narratives and space management philosophy to consumers. During public relations events, they provided media contact and offered practical marketing management suggestions to enhance the crowdfunding process step by step.

Crowdfunding allows proposers to directly face the market and consumers. Eliminating intermediaries can lead to more transparent and open markets. This important shift impacts not only those proposing projects but also crowdfunding participants. They become aware that their consumer behavior can help reduce market inequalities, which validates their actions and strengthens their willingness to support the crowdfunding projects they believe in. In short, when consumers support organizations or products through crowdfunding, they feel they are not just buying a product; they are also backing the values and philosophy that the product embodies. This connection makes them more inclined to invest time in promoting the products to others. This interaction isn’t unidirectional—during crowdfunding, consumers aren’t merely passive information receivers. Proposers can assess market demand for their products by analyzing consumer participation levels during fundraising and use consumer feedback to promptly adjust project details.

Storytelling is essential for proposers involved in crowdfunding. It’s even more effective if fundraising campaigns can extend beyond comfort zones and engage audiences who typically don’t pay attention to these issues. Converting crowdfunding energy is essential for attracting attention to projects, achieving fundraising goals, and becoming a significant force in organizational development. This challenge tests both project proposers and professional fundraising consulting platforms. Ultimately, regardless of the outcomes of crowdfunding, it can act as a significant symbolic indicator for participating organizations to assess their future competitiveness or levels of support.

Cross-industry Collaboration Risks

In this era of contracting, outsourcing, and a growing number of portfolio workers, cross-departmental collaboration within organizations and external collaboration across different industries is increasingly prevalent. Collaboration across industries enables diverse professionals to showcase their strengths while inspiring one another creatively. When both parties are unfamiliar with each other, trust issues and doubts regarding each other’s professionalism can significantly impact their ability to work together effectively. This often leads to differences in work values emerging during collaboration. Additionally, varying thinking patterns and approaches to problem-solving can present common challenges in cross-industry partnerships.

Everything has multiple perspectives that vary depending on the observer and circumstances. Similarly, cross-industry collaboration has its dual nature. Lightbox and “Backer-Founder” represent two distinct groups: non-profit arts spaces and goal-oriented consulting companies. These organizations operate under fundamentally different modes of project execution, rhythms, and thinking processes, sometimes even heading in opposite directions. Given the vast differences, friction during collaboration became inevitable. When Lightbox members collaborated with the “Backer-Founder’s” project team, they consistently reminded themselves to set aside their internal struggles and various artistic preferences.

Crowdfunding platforms emphasize project management and efficient processes, requiring adherence to schedules. In contrast, artists in non-profit spaces approach their work more flexibly, allowing for adjustments based on circumstances. Based on trust in the platform consultants’ marketing expertise, Lightbox learned marketing integration skills for new products while producing content during collaboration.

For Next Time

Crowdfunding provides a direct link to communities. Marketing and advancing fundraising projects, along with helping consumers understand the public nature and significance of entire projects or organizations, is the first step toward encouraging participation. If crowdfunding projects can reach communities that were previously overlooked, it represents another step forward.

Before executing fundraising plans, team leaders must understand their team’s current status, carefully evaluate limited internal resources and personnel allocation, assess the feasibility of project execution and its public impact, and set reasonable goals. Team members also need to adjust their attitudes. During crowdfunding, new work modes and unfamiliar crowds pose significant challenges to the team’s stress resilience, work dynamics, and adaptability. The knowledge gained from crowdfunding and cross-industry collaboration significantly enhances team growth, fostering the development of diverse possibilities in the future. “Crowdfunding game rules are oligopolistic. As arts workers, you must learn to creatively use this tool,” said director Tsao Liang-pin. Effectively utilizing new technologies and concepts to capture the scattered attention of audiences has become a significant challenge for contemporary arts spaces.